The fundamental purpose of urban design is to provide a framework to guide the development of the citizen. As this AR campaign reaches its conclusion, the penultimate essay attacks the City of Doing found in modernity

In the largest-ever wave of human migration, vast numbers all over the developing world are flooding from countryside to city. Most of humanity is now urbanised as new settlements, some expanding into vast megacities, mushroom rapidly − and around them sprawling slums provide the initial foothold in the transition from peasant to urbanite. Many of these new cities, like the newer parts of old ones, are dismal aggregations of sweatshop factories and crowded residential buildings of stacked hutch-like homes. But, like the even less salubrious slums, these offer escape from the grinding poverty of the countryside, with its lack of education and healthcare. The first generations entering these cities and slums willingly sacrifice their lives to give their children the education and opportunities they never had and to support dependents in the countryside. And despite the slums’ decrepit and unhealthy conditions, they do in a sense ‘work’: people progressively upgrade their homes, or move on, as they can afford to; and the slums are hotbeds of small-scale entrepreneurship and creativity. Indeed it is well-intended interventions, such as construction of state-funded new housing, that tend to fail. Slum dwellers cannot afford the rents and implicit lifestyle of the new housing, whose leases secretly fall to the better off to be sublet for profit.

Seemingly somewhat contrary is the ongoing trend in developed countries for cities to focus on improving their open spaces and quality of life. Influential examples are the transformation of Barcelona, initiated by Oriol Bohigas in the 1980s as advisor on urban affairs to two consecutive mayors, and the Slow City (Cittaslow) movement originating in Italy. Such developments are characteristic of wealthier countries with relatively stable or even declining populations. Besides improving the quality of life in cities − making them better places for leisurely enjoyment, so less stressed and in various ways healthier − the spreading Slow City movement also emphasises enhancing local characteristics and culture, including regional food and cuisine. It thus resists the homogenising impact of globalisation. Yet precisely because of this it also makes a city more attractive to skills and investment in our globalised world, where cities as much as countries compete for these economic essentials, and key assets are a city’s quality of life and individuality of character.

The most important and influential of current developments goes further. This is the Transition Towns movement now spreading rapidly through the towns and cities of much of the world. Its primary emphasis is on building local resilience, and so sustainability, through a wide range of community and environmental initiatives. Although there is much to be learnt from this movement, it is tangential to the focus of this essay. But it is strange how few architects participate in the movement and that when mentioned in architectural schools, even those within a very active Transition Town, neither students nor staff tend to be aware of this. Part of the problem seems to be architects’ reluctance to dismount their professional pedestal and muck in as equals with ordinary folk more knowledgeable and committed than themselves.

Rising rapidly all over the developing world are cities of tall towers and surrounding slums

Much about the future may be impossible to predict, not least because of rapid technical innovation and, particularly, the continuing exponential increase in computing power in accordance with Moore’s Law. How many of today’s gadgets and the way they have affected daily life could have been envisioned a couple of decades ago? But other assumptions about the future seem pretty safe bets, including those underlying this series of essays, not only because they are founded on discernible trends, but even more so because they are urgently necessary to resolving a wide range of dangerously pressing issues. The most threatening of these, as earlier essays have argued, are endemic to modernity. And resolving them would require, among other things, counterbalancing modernity’s too exclusive focus on the quantitative and objective with attention also to the qualitative and subjective, including the desire to live in accord with personal values and aspirations.

Without this, for reasons also argued in earlier essays, progress towards sustainability will remain elusive. Hence trends like the Slow City and Transition Towns agenda, as well as the sort of urban design advocated in this essay, are certain to prove germane to the exploding cities of the developed world, to which all such concerns currently seem utterly alien. Rural people arriving in the cities might willingly sacrifice themselves for dependents and future generations; but their children and following generations will inevitably have, and want to realise, very different aspirations. Nor will being able to afford consumer goodies and distracting entertainment persuade them to compromise their ideals. They will want lives and work of dignity, offering meaning and personal fulfilment − what the city always promised, but delivered to only a minority, and will soon be deemed essential by most. So the challenges facing these mushrooming cities are much more than the overwhelming current concerns of number and quantity, such as housing and employment for their burgeoning populations, feeding them and disposing of wastes and emissions. Difficult as these are to achieve, they are conceptually easier to entertain than dealing with such psycho-cultural challenges as conceiving of cities that offer lifestyles and work of dignity, meaning and fulfilment in line with very varied individual notions of purpose, identity and personal destiny.

In the light of all this, the current assumption of more and more of us living in cites and mega-cities seems less than inevitable. Besides, in times like these when we are undergoing massive and pivotal historic change, it is as likely for some trends to reverse as to continue. For instance, many analysts and commentators have been warning of problems of future food supply and security. Our current systems are heavily dependent on oil for farm machinery and transport, fertilisers and pesticides. Even though Peak Oil no longer seems the looming challenge many assumed until recently, our energy-intensive agriculture is problematic for, among other things, the emissions produced, the poisoning of land and water, the loss of biodiversity and the un-nutritious food produced. Its unviability and the need to offer millions dignified and meaningful work suggests there may be a return to the land, to small-scale labour-intensive farming, to regenerating and living in harmony with the earth and its daily and seasonal cycles, to producing local nutritious food and leaving a long-term legacy for one’s descendants. After all, the poverty presently associated with such farming has been brought about by the corporations that are trashing the planet to maximise profits by driving down prices and feeding us highly processed, unhealthy food. What is being suggested here is not the end of cities, but rather that the future might lie with a range of differing kinds and sizes of settlements, some no doubt of a sort yet to be conceived. After all, thank to the Internet and various forms of energy-efficient public and private transport, combining the best of urban and rural life is now perfectly possible.

‘Trends like the Slow City and Transition Towns agenda, as well as the sort of urban design advocated in this essay, are certain to prove germane to the exploding cities of the developed world, to which all such concerns currently seem utterly alien’

Besides, although global population is projected to continue to grow until mid-century, when it will reach between nine and 10 billion, some analysts now say it will not only plateau but then start to dwindle. Wherever women have become educated, population has stabilised and in some countries declined as birth rates fall below replacement levels. This is a pattern, it is argued, that is bound to be repeated globally. Yet it could be that declining birth rates are a consequence not only of female education but also of mothers having to work in our neo-liberal economies. Countries with good childcare provision, like Iceland, see less of a drop in birth rates. Anyway, the likelihood is that the population pressures of the present and near future may be relatively short term. From an evolutionary perspective, this population bulge could be seen as a way to further pressurise humankind to make the next jump in its own evolution − from modernity to trans-modernity, from wanting to conquer or suppress nature to seeking symbiosis with it, crucial steps towards sustainability. So, much of the squalid urban fabric built this millennium may soon come down, both because of declining populations and so as to create more liveable cities better suited to future aspirations and the true purposes of cities − something the design of these mushrooming cities maybe should already acknowledge.

Climate as a determinant of design: a narrow shady street that channels breezes in Foster + Partners’ design for Masdar City, Abu Dhabi

The challenge of sustainability will increasingly influence urban planning and design, as it does already in the advocacy for the Compact City − dense with mixed-use neighbourhoods to encourage walking, lessen the need to commute and make public transport feasible − and prioritising construction on brownfield rather than greenfield sites. Computer modelling and use of suitable planting can lead to improved microclimates: by channelling cooling breezes and excluding gusty downdraughts, for instance; by planting roofs to shade them and aid transpiration; by using deciduous plants for summer shading of streets and facades; and so on. Besides improving external microclimates, such measures reduce loading on mechanical equipment within buildings or help to eliminate it entirely. These and other pragmatic measures are widely known and discussed, and so need no elaboration in these few pages. Nor do such similarly significant ones for saving and recycling water, enhancing biodiversity and providing refuge for wildlife and corridors for its movement.

City of Doing: Le Corbusier’s masterplan for St Dié consists of object buildings dispersed in landscaped open space – a city fragmented into differing things done in different places

Another important factor beginning to receive attention in urban design discussion is human health, and not only by maintaining cleaner air and water and minimising the many environmental toxins ranging from vehicle exhausts to off-gassed chemicals from buildings. The epidemic of obesity and associated diabetes are due partly to the processed foods with which corporations swamp supermarkets and fast food outlets, but also because in the contemporary city, hours are wasted commuting long distances rather than walking or cycling in pleasant conditions. Another contributory factor to many diseases is increasingly understood to be inflammation, often compounded by the solitary lifestyles, loneliness and lack of community characterised by modern city life and exacerbated by its design. These are issues we will return to in next month’s essay.

Two other developments already raised in an earlier essay will also in time impact profoundly the life and design of urban areas. First is the ongoing emergence of what Daniel Pink has labelled the Conceptual Age.1 Second is progress towards what Jeremy Rifkin refers to as the Third Industrial Revolution2 (TIR) − if politicians can be persuaded to stop fighting to preserve the corporate behemoths of the Second Industrial Revolution (SIR) and the privileges of those at the top of their pyramidal command structures, all at the expense of most of us and the emerging TIR. Pink notes how following the migration of rote manual labour (factory work) from the developed to the developing world, and so the transition from the Industrial to the Information Age, rote non-manual or intellectual (linear sequential, left-brain) work is now following: call centres, accounts, even legal advice and medical diagnostics. Now, as wages in these countries and transport costs increase, some manufacturing is returning to the post-industrial developed world. Nevertheless, in our progression from the Information to the Conceptual Age, our cities are refocusing their economies on creativity, culture and caring (all drawing on right-brain capacities of empathy, pattern recognition and so on) − caring because required by our ageing populations, and culture to cater for the long post-retirement portion of the lives of an educated citizenry. This suggests cities combining the buzz of the very best contemporary cities with the virtues of the Slow City.

City of Being: The Nolli plan of Rome shows a city of contiguous fabric, with the open space as the figure against the ground of buildings, a city in which you are immersed and exposed

Redefining purpose

Behind all these essays, as already explicitly stated and argued in them, are key assumptions. Central to these is that in this pivotal moment in history several epochs of differing duration are drawing to a more or less simultaneous close, in particular 4-500 years of modernity along with its terminal, meltdown phase of postmodernity. The emergence of the Conceptual Age and TIR are part of this larger transition. Thus the times demand that much be radically rethought, right down to such basics as the fundamental purposes of things. This is especially true of architecture and urbanism because the Modernist conceptions of their purposes, along with the associated vision of what constitutes the good life they are to frame, are so desperately impoverished. In contrast to their too-exclusive emphasis on the objective, the Right-Hand Quadrants of the AQAL diagram, it is time to re-emphasise the many dimensions of human subjectivity, the Left-Hand Quadrants, and to reground architecture and urbanism in these too. Their fundamental purposes need redefining in terms of their deepest, originating human impulses to be as inspiring, ennobling and encompassing as possible so as to inspire urgently needed change.

‘Certainly the city is a place of trade and manufacture, residence and recreation, education and welfare. But the quintessential and most elevated purpose of the city is as the crucible in which culture, creativity and consciousness continually evolve’

Among the most memorably taunting of the graffiti slogans of Paris ’68 was ‘Métro, Boulot, Dodo’, life reduced to a meaningless, relentless round of commuting, work and sleep. Terrifyingly, this is an exact and fair summary of the Functional City of modern town planning as promulgated by the Athens Charter: urban settlements of dispersed zones for work, housing and recreation connected by circulation-only transport routes. This is human life reduced to a mere productive economic unit, its pointlessness to be compensated for by the addictive distractions of consumerism and entertainment. Indeed, the underlying ethos of such planning was a weird mixture of socialism and consumerism, seeking a balanced allocation of requisite facilities: one playground per so many houses; one primary school per multiple of that many houses; and so on. Town-planning manuals of the mid-20th century exemplify this dismal approach exactly and in many parts of the world towns and cities were laid out like this. The insidious legacy of this thinking continues, if often more subtly.

This modern Functionalist City is what I described in an AR essay of a few years back as the City of Doing, as opposed to the City of Being.3 It is a city shaped only by the seemingly rational, objective concerns of the Right-Hand Quadrants. At its not-infrequent extreme, it is a city of freestanding mono-functional object buildings dispersed in mono-functional zones and to which access is gained by movement-only channels lacking all the social dimensions of the traditional street − what in a much earlier AR essay4 I described as the ‘wiring diagram city’. This is a ‘city’ in which not only is urban fabric fragmented, but so is civic life and the psyche of the citizens. In it life breaks down into discrete and discontinuous roles dispersed between different locations (home, workplace, sports field) requiring different modes of behaviour (parent, employee, athlete or fan) all isolated in a conceptual and spatial void, through which you travel in the encapsulated anonymity of car or public transport. In such a city nobody is known in their entirety, the reductionist and mechanistic conception of the layout resulting in the avoidance of community entanglements and chance encounters, with their complexities and contradictions that provoke self-reflection, so leading to self-knowledge and psychological maturation.

Certainly the city is a place of trade and manufacture, residence and recreation, education and healthcare, and so on − the things the city of modern planning provided for. But the quintessential and most elevated purpose of the city is as the crucible in which culture, creativity and consciousness continually evolve. Consistent with this view, some archaeologists now speculate that the initial origins of the city are not as a place of trade but of large religious gatherings, and that it was the need to feed these that provided the impetus to produce agricultural surplus. The city remains the best, but not only, place to become fully developed as a human by today’s understandings of what that means, and where tomorrow’s understandings of what that will be are being forged. To do this, the city must cater to the very different needs and aspirations of its citizens through all ages and stages of life, from dependent infant and then exploring child through to adulthood and families to old age. Adding yet further complexity to this is that the city is now home to many cultures, to some of which it is a melting pot while others wish to retain their particular traditions and lifestyles. It is in helping to understand these diverse world views and their underpinning values, as well as in how best to accommodate and communicate with these groups, that disciplines like Spiral Dynamics are proving invaluable to architects and urbanists − no matter how much their schema of developmental levels is offensive to the postmodern mindset.

Hence the fundamental purpose of urban design isto provide a framework (spatial, functional, circulatory, economic, legal etc) to best guide the development of the citizen as well as the city or urban area. It is about the interdependencies and mutual development to fulfil the latent potentials of citizen and city by elaborating as richly and coherently as possible the many different places of the city and so also of the lived experience of its inhabitants. It is an art of space, time and change or maturation. Time here includes the cycles of day and season, the lifespan of citizens as they grow and mature. Time also includes the long unknown future in which cities and culture evolve and change as is healthy and inevitable, and in which buildings will come and go while the city nevertheless retains much of its unique character and identity. As with our redefinition of the purpose of architecture in an earlier essay, this returns to the centre of design consideration our full humanity, from where it was displaced and trivialised by elevating Functionalism, the quantifiable and the objective, at the expense of qualitative realms of the cultural, experiential and psychological. A city of such reinvigorated purpose would be rich in experiences and things to do and explore, and through this develop your personal interests and capacities, as you are socialised and develop empathy in interaction with community and other cultures. Such thoughts confirm how impoverished is much modern and contemporary architecture and urbanism. Yet we have become accustomed to a world of compact and mutely rectangular pieces of electronic equipment of extreme functionality and user-friendliness. If only more buildings and urban design could emulate this instead of indulging in whizzy forms that deliver next to nothing.

Development of urban design

Although the legacy of modern planning still lingers on, its weaknesses were soon obvious to some. In the 1950s this led in the USA to the formation of urban design as a discipline that would act as a bridge between the abstractions of planning and the individual buildings of architecture, providing some context for the latter to respond to and embed themselves in. The first urban design course anywhere was initiated by Josep Lluís Sert when Dean at Harvard. But the approach most germane to our argument here, which will be expanded upon later in this essay, was that taught by Professor David Crane as the Civic Design Program at the University of Pennsylvania in the late 1950s and 1960s. Although many of the best urban designers studied under Crane or ex-students of his, this approach and its legacy have been too soon forgotten, perhaps in part because Crane published little. Complementary to Crane’s teaching, and hugely influential as a critique of Modernist planning, was Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities of 1961 and, to a lesser degree, the later The Uses of Disorder by Richard Sennett of 1970, which still deserves wider attention by architects. Both these books are largely about the being and becoming dimensions of urbanism, as was much needed then and still is today.

World Squares for All, a remodelling of London’s Trafalgar and Parliament Squares and Whitehall which links them, by Foster + Partners with Space Syntax as consultants.Trafalgar Square, the classical centre of the ex-Empire, with architecture derived ultimately from the Roman imperium, is now made pedestrian accessible with new stairs up the pedestrianised street in front of the National Gallery

Jacobs’ book helped fuel the backlash against modern planning and urban redevelopment among the many who were appalled at the destruction of historic buildings and neighbourhoods. This led to the conservation movement and contributed to Postmodernism, which offered cogent if too-narrow critiques of modern architecture and planning, decrying abstract object buildings for their lack of relationship to context, history and even the street wall. These themes were taken up in Europe by the postmodern Neo-Rationalists who advocated returning to the traditional typologies of street, square and urban block. And their architecture, even if somewhat abstracted, was also based on and evoked traditional typologies so as to, supposedly, be rooted in and carry forward the past. Together these debates − if not the often ghastly architecture that resulted − definitely had a beneficial impact and brought to the work of many architects a new sensitivity to history, context and civic responsibilities, leading to the belated maturity of some late-modern architecture.

Another significant development was the publication of A Pattern Language by Christopher Alexander et al. A book packed with ideas and wisdom, it certainly has its weaknesses, particularly the constructional patterns. Architects are also put off by the implied return to craft construction of a rather crude sort, and the retro formal language. But it is very much a book about the City of Being and Becoming, of richly articulated and varied places that will nourish and develop the psyche and a richly vibrant community life, and in which even buildings and urban spaces convey a sense of life, almost as beings in themselves. It is a book whose time has yet to come, particularly as it plays an important role for times of profound cultural change by sifting and condensing into a usable formula the wisdom of the past so that it can be carried forward to influence the next era. A very different, and superficially almost antithetical, development is the emergence and increasing use of the analytic, computer-exploitingtechniques of Space Syntax.5 This is a set of narrowly Right-Hand Quadrant techniques that provide a powerful predictive tool both for analysis prior to design and for checking proposals as they are being developed. Although immensely useful, Space Syntax lacks the breadth and attention to all the Left-Hand Quadrants concerns of the David Crane approach. Besides, Crane had developed strikingly similar graphic techniques for analysing movement patterns that, if lacking the precision of Space Syntaxes computer-dependent methods, are not only far less narrow but also help designers to gain a deep feeling for the forces at work around and within the area under consideration.

South Kensington’s Exhibition Road shows scant regard to context

Shortcomings of current urban design

A problem with much urban design is that it is still infected with modern, Functionalist thinking − too limited to the Right-Hand Quadrants. This is particularly obvious in schemes of blanket zoning and mono-functional components, such as traffic-only streets and single function buildings − masterplans of a sort still being produced. To oversimplify to clarify a point, let’s contrast two opposed approaches to urban design. One prioritises zoning, and the allocation of functions and facilities in predetermined ratios, served by transport links. The other shapes movement and public space into a spatial armature made up of many different kinds of places (streets, alleys, squares, parks etc) articulating a range of qualitatively different locations, each suited to a range of functions. Compared with the former, this approach is more flexible, both in allowing choice in the kinds of buildings erected initially and for these to be rebuilt over time while the spatial armature ensures some continuity of character and identity. If the former has its roots in the modern City of Doing, the latter tends towards the City of Being, the model to which historic cities conformed.

The difference between these approaches can be found in what at first may seem similar enterprises. Contrasting examples are Mayor Ken Livingstone’s project, initiated by his advisor Richard Rogers, to furnish London with a series of new public spaces, and Foster + Partners’ pre-Livingstone and only partially implemented scheme, World Squares for All.6 The first of these creates trendily designed spaces with little regard for context, or making meaningful connections with the past, such as the repaved Exhibition Road in South Kensington; except at its southern end, this lacks the adjacent uses and dense hinterland to bring it properly to life. Although the best known, this is by no means the most misguidedly conceived of these spaces.

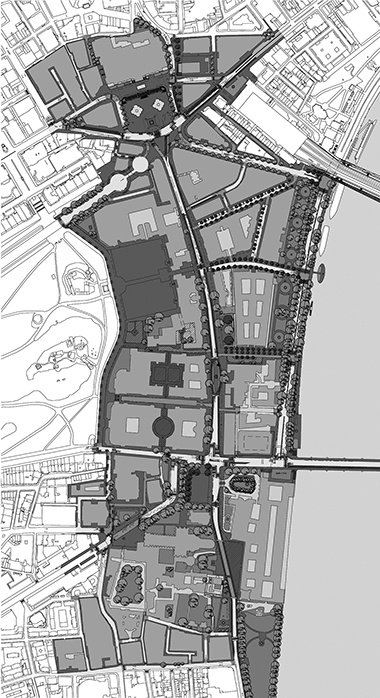

Masterplan for whole World Squares scheme with Trafalgar Square to north and interlocking green spaces around Parliament Square resembling an English cathedral close

World Squares for All, designed with analytical input and advice from the Space Syntax consultancy and traffic engineers, is very different. It draws on careful study of context to draw together into a new whole two of London’s major public spaces, and makes these more pedestrian-accessible by closing streets on one side of each to vehicular traffic. Equally important is that the scheme intensifies the contrasts, symbolic meanings and connections to history of both spaces. Stone-paved Trafalgar Square is Classical (faced by the Neo-Classical National Gallery, St Martins-in-the-Fields, Canada House and the cod Cape Dutch Classical of South Africa House) and adorned with statues of military heroes, as befitting the centre of what was Britain’s Empire. In complete contrast, the area around Parliament Square was to be a softly green and leafy sequence of interlinking spaces, redolent of that peculiarly English urban form, the cathedral close, and flanked by the Gothic Westminster Abbey and St Margaret’s Church and the Neo-Gothic Houses of Parliament. Connecting these centres of Empire and England is the refurbished Whitehall, whose slight curve obscures one from the other, with the Privy Garden as an enticing mid-point visible from both. Foster also proposed that these spaces be linked by further upgraded pedestrian connections to other monuments in central London as part of his concern with ‘wayfinding’, helping visitors to orient and find their way around. The whole scheme therefore is about connections, not only spatial and pedestrian but also to history, thus attending to the cultural dimensions of the Right-Hand Quadrants. Sadly Livingstone and his team failed to grasp this and asked other designers to hard-landscape only the central space of Parliament Square, which his successor Boris Johnson rightly scotched. Although this does not apply to World Squares, it seems that a weakness of much current urban design is that it is undertaken by architects untrained in, or without a deep understanding of, urban design. Such schemes often look orderly and well-organised at first glance, but closer inspection reveals no deeper ‘structuring’ logic. One weakness is an essential lack of understanding of how movement, its density of flow and character, generates adjacent uses (particularly retail) and provides the framework that animates and articulates the scheme and ties it into its context. This becomes apparent when it is impossible, from study of the movement network, to predict the location of land uses (functions) and relative land values. Missing too seems an understanding of the many temporal dimensions urban design must deal with. Besides the cycles of the day, there is phased implementation that should generate its own momentum towards completion. And then the various physical elements each have different lifecycles: major ones such as boulevards and parks that give the primary order and identity to an urban area last centuries; minor streets and lanes might be adjusted over decades; and buildings come and go in various cycles. Good urban design is thus not only spatial, it must also be highly strategic. It is thus an art of tersely understated synthesis, yet has also to be suggestive enough to both invest a scheme with character and to elicit from architects a rich array of appropriate responses over time. This capacity to allow yet condition change is a hallmark of good urban design, something that often only the trained and experienced eye can judge.

‘That urban design is taught only very cursorily if at all in architectural schools − or is replaced by superficial exercises in ‘mapping’ and so on, or offered only as an elective or masters course − is a scandal’

Currently fashionable approaches such as parametric urbanism and landscape urbanism exhibit all the above flaws. To reintroduce landscaping and nature into the city as fairly dominant elements is for many reasons admirable − benefiting bio-diversity and wildlife, controlling flood waters, tempering the climate, providing a recreational environment for a range of outdoor pursuits and sport, and so on. But as with Parametricist schemes, most urban landscape ones fail for their lack of the urban dimension, such as how movement generates land uses and how the movement network can be articulated to create a variety of locations that are qualitatively different just by

virtue of their location in that net, prior to any further elaboration. The roads in such schemes may wiggle, the blocks may distort in blobby forms, but many of these schemes lack essential variety, each location being boringly much the same as any other.

Methodology

That urban design is taught only very cursorily if at all in architectural schools − or is replaced by superficial exercises in ‘mapping’ and so on, or offered only as an elective or masters course − is a scandal. This may reflect a shortage of the requisite skills to teach it, particularly in the studio, and is apparently also yet another dire consequence of the Research Assessment Exercises: these undervalue design as something woolly and un-academic, leading to the erosion of spatial urban design in favour of the a-spatial abstractions of sociologically oriented planning. A thorough grounding in urban design undoubtedly makes for better architects, more alert to the wider responsibilities and impacts of their designs, and better able to analyse the needs and potentials of the surrounding area that the building should address and capitalise upon. Moreover, any training in urban design would better prepare architects to undertake large-scale projects, as well as to appreciate a good urban design scheme when confronted by it and help understand how to respond to it architecturally.

Another benefit is that familiarity with urban design would make architects more aware and disciplined as designers generally. Urban design operates on a larger spatial canvas than architecture and must consider longer time periods in which it involves and impacts upon major capital investments. Design is thus an iterative process involving wide-ranging research and following a rigorously disciplined sequence.

An example of an urban-landscape masterplan: ‘Deep Ground’ plan for Longgang in China by GroundLab and Plasma Studio in collaboration. Despite the wiggly roads and distorted blocks, the configuration of movement and green space system provides little inherent diversity of character and location

The architectural design process may start from many points simultaneously, including working from the general, such as context, down to the particular, and vice versa, thinking about suitable materials and their detailing and working upwards. Often a better understanding of the problem and what the architect should be striving to achieve only emerges during design. By contrast, urban design tends to proceed from the general to the particular, starting with research and analysis. Then before design starts, or after only tentative exploratory forays to test potentials, clearly stated goals are formulated to guide design, and against which to check whether the design will deliver. This discipline is essential to achieving a terse yet immensely inclusive synthesis whose understated forms are nevertheless pregnant with many potentials for responding to and elaborating upon what are usually only subtly suggestive cues crafted by the urban designer.

‘A city is both a cultural artefact, consciously and wilfully shaped by humankind, yet also a living organism unconsciously shaped by its own internal metabolic forces’

The particular approach briefly sketched here described as if for redeveloping or reworking an existing urban area to be part of a 21st-century City of Being, derives from that created and taught by David Crane and his colleagues more than half a century ago. It is one of those now-forgotten developments worth resurrecting, carrying forward and updating as part of the necessary Big Rethink. It recognises that a city is both a cultural artefact, consciously and wilfully shaped by humankind, yet also a living organism unconsciously shaped by its own internal metabolic forces. From the former comes much of a city’s grandeur and identity, from its boulevards and urban set pieces of squares and monuments − although sometimes topography contributes too, as in extreme examples such as Cape Town and Rio de Janeiro. From the latter, as an organism, comes a city’s viability, vitality and resilience. Designers need to keep the former in mind, that the city is a cultural artefact, and part of the initial research − particularly if undertaken by foreign consultants − may sometimes include study of the local culture and customs. If a large-scale project, research might also start with investigating the natural features and forces that partially shaped both these and the city − topography, geology, hydrology, climate, ecology and so on, as well as the interdependencies of the city and its bio-regional hinterland.

More usually analysis will concentrate on understanding the organic dimensions of the city, a process which often includes charting its historical development (so explaining many of its particular quirks) and understanding the area to be masterplanned in relation to this history. It is particularly important to understand the movement system, the lifeblood that

both serves and generates the land uses and much of the character and identity of the city. Crane developed a graphic technique for abstracting and so clarifying the role of each component of the movement network, giving much the same information as Space Syntax. But his technique also indicated something of the particular nature of each element, not only the intensity of movement it channelled but its character as, say, a ‘through way’ or ‘activity street’ such as that flanked by retail. As with Space Syntax, this technique also ensures that the eventual design is seamlessly stitched into the surrounding city, and perhaps extends and brings to fruition latent potentials it uncovers there. Also very important are the fine-scale surveys of land use, land value and building condition. After a period of studying the movement diagrams, along with aerial photographs, you develop a remarkably vivid feeling for the life of the city-organism, almost as if watching a slowed-down amoeba under a microscope. You can see how it is changing and why, which bits are healthy and which are blighted, and get a good sense of what is required to regenerate a blighted area, such as channelling movement through or away from it. A key aspect of urban design is learning how to work with these metabolic forces, letting some continue or even encouraging them, and redirecting others, perhaps by subtly manipulating their momentum.

To complement this Right Quadrant approach, various exercises can be undertaken to get insight into the subjective experience and perceptions of the locals as well as of their problems and aspirations − the Left Quadrants. These are often facilitated using a wide range of procedures developed since the days of Crane’s programme but fairly widely used in workshops and meetings such as those of Transition Towns. What is important and meaningful to the locals is often markedly different to what the detached professionals might assume. Inevitably, different age groups have different perceptions and desires, and in our multicultural cities the contrasts between what different cultures value can be striking. This phase tends to produce invaluable knowledge, and also initiates the participation of members of the local community in order to better

serve them and help them acquire a sense of ownership.

Once all this research is well under way, and there is a good understanding of the objective pressures and potentials as well as the subjective concerns of the community, the urban design team can start to consider what form their intervention might take. As the initial step, goals are carefully formulated: both general goals for the whole project and others for each of its subcomponents, such as the street system, planted open spaces, positioning of public facilities and so on. These are then presented to and discussed with locals, municipal officials and members of the business community to further elaborate, revise and refine them. Again this is one of the key participatory phases of the process that sometimes leads to considerable reorientation in the ideas and intentions of the professionals. Only after this does design begin in earnest.

The primary focus of design is on what Crane called the Capital Web, a valuable term that has fallen out of use. The closest contemporary equivalent is armature, but this seems to mean somewhat different things to different designers. The capital web encompasses the total public realm − the streets, squares, parks, public buildings and public transport systems − all things paid for and used by the public. The elements on which design attention is initially focused are the movement and green space networks. In what has become almost a norm, the green space network of parks and other planted spaces tends to be elaborated wherever possible into an alternative system for moving around, independent of and interwoven with the main movement system of streets and pavements.

The aim is to configure the capital web into as richly varied a system as possible and appropriate. This is done by teasing apart the movement and green space systems into subcomponents (each a place in its own right), creating hierarchies of different size, character and intensity of use (through, say, boulevard, street, residential road, lane etc and, say, large park, sports fields, greenway, pocket park, playground etc) and then interweaving these to create a complex yet coherent framework of many kinds of public places. Where these cross are points of intensity and potential encounter, a whole range of qualitatively differentiated locations suggestive of and suited − functionally, experientially and even symbolically − to various kinds of uses, which can each find their appropriate place. (Each place, though, might be suited to a relatively limited range of uses: hence a site axially located at the end of a main street may be suited to ceremonially civic, religious or community use.) It is this framework or armature that invests legibility, identity and choice and that persists through time with buildings being built and demolished around it, while it too changes somewhat yet ensures some recognisable continuity of visual and experiential character.

‘The city remains the best, but not only, place to become fully developed as a human by today’s understanding of what that means, and where tomorrow’s understandings of what that will be are being forged’

The art of urban design goes further than configuringa framework of many diverse places and locations: it also has to give subtle cues as to how architecture can respond to, complete, enhance and give meaning to this richly varied public realm. Of course, many architects don’t respond to such cues, whether because they are diehard Modernists concerned only with the internal workings of their mutely abstract object-buildings, or because they equate being avant-garde with deliberately breaking rules. So part of an urban design might be a set of guidelines to be complied with. These might restrict to a limited range the functional types of buildings to be built in certain areas, stipulate plot ratios, cornice heights and that the buildings should follow the back-of-pavement for a percentage of its frontage. Besides visual and spatial reasons, there are other advantages to such guidelines, in that they might ensure a match between the capacities of the various forms of infrastructure and the loadings imposed by the buildings. And sometimes guidelines go much further in stipulating cladding materials, percentage of window to wall, ground floor arcades and so on. Until architects acquire a more mature and expanded design ethos, which values the city at least as much as their own building, that seems fair enough.

| Checklist of some urban design criteria, particularly applicable to the ‘capital web’: | |

|---|---|

| Context | A prime shaper of urban design is the larger context, to which it must connect but also provide for some of what it lacks, making the most of the various opportunities this may present |

| Configuration | Urban design is the art of creating a richly configured armature or ‘capital web’, of movement and green space systems interwoven to create as many qualitatively different places and locations as possible |

| Change | This armature is designed to persist over time yet allow the elements adjacent it to keep changing, while it both retains a certain consistency of character and identity, and itself changes − through, say, increased intensity of use, resurfacing and gradual acquisition of monuments |

| Continuity/connection | The armature both extends elements in the surrounding city into the site − so that the scheme is an intrinsic part of the city, not a disconnected island within it − and ensures these continuities over time. A major role for urban design today is to connect up again the fabric of the city fragmented by modernity and also to forge new connections with nature as a multi-functional resource and for spiritual succour |

| Character | The armature or capital web is designed not only for function and flexibility but also to confer memorable character and identity, which may enhance quality of life and confer a competitive advantage over other cities in attracting skills and investment |

| Ceremonial/civitas | A function of the city, overlooked by the Functional City, is to host various kinds of ceremonies of differing size, as enhanced in places of suitable civic character |

| Choice | A richly configured armature or capital web creates choice between a variety of kinds of places, which can each host various functions and afford a range of experiences and interpretations as to their meanings. This is a fundamental purpose of the city |

| Contrast | This is most easily created by designing in as many contrasts as possible, between such things as: big and small; busily noisy and quiet; hard surfaced and verdantly shady; openly overlooked and private refuge; and so on |

| Comprehensiveness | Urban design strives to provide as wide a range of functions and experiences as is appropriate, recognising all the different ages and stages in people’s lives that it must host, along with the various cultures and customs characteristic of today’s cities |

| Coherence/comprehensibility | To orient people and be best used, an urban design needs to be ‘legible’, easily read and remembered in its geometric configuration and internal logic |

| Cues | Crucial to the art of urban design is ensuring the armature, though understated to enhance long-term flexibility, also be subtly suggestive of how architects might respond to and complete it |

| Community | Modern architecture and urban design tend to undervalue and be unsupportive of community, which remains essential for such things as fully socialising children and helping adults achieve self-knowledge and psychological maturity |

| Conflict and contradiction | A great benefit of community is that the inevitable conflicts and contradictions encountered erode the ‘pure’ or fantasy sense of identity that can be a consequence of modern-city life as lived fragmented between and encapsulated in the independent protocols of the City of Doing |

| Culture and customs | Certain once-local cultural traditions are becoming global, particularly the Mediterranean lifestyle of alfresco dining in public and so on. Yet cultural traditions − of decorum, privacy, gender roles etc − can be major determinants of urban form, particularly of the shaping of the public realm and its uses |

| Climate | Along with microclimate − and its modulation by topography (as, say, in night-time temperature inversion) − can be a major determinant of the armature’s design, affecting width and orientation of spaces, degree of shading and admission of sun and so on |

The example of Auch

Looking for illustrations for this essay turned up a number of perfectly decent urban design schemes that nevertheless don’t demonstrate the full richness an approach such as this can result in. An ideal that often comes to mind is the compact historic centre of Auch in south-west France. Within a small area it has an extraordinary range of quite different interlocking spaces, each very aptly related to the civic buildings that face it, and that together offer a very full panoply of the experiences urban life has to offer. Prominent in the plan of the city centre are two squares of more or less the same shape and size centred on circular pools of identical size. One square, alongside the cathedral and where the medieval cloister once was, overlooks a steep slope and grand stair down to the River Gers and the countryside beyond. It is shady, quiet and contemplative, showing how the essential character of a place can persist through even dramatic change. A murmuring water spout is the fountain in the middle of the large pool, making just enough sound to enhance the sense of quietness. The other square is 19th century and a traffic gyratory on the main vehicular route through town. Here the fountain is a boisterously splashing affair to assert its presence above the traffic noise. The square is flanked by cafés, a fine hotel and the town hall that confronts, across this square and the long splay-sided market square, the main facade of the cathedral, this relationship made possible by the skewed alignment of the two squares. A smaller splay-sided square directly off the market square sets off what is the library at its end while steps up from the gyratory square lead to a long esplanade shaded by rows of plane trees and on clear days offers views of the Pyrenees. The long axis of the esplanade is marked by a wider gap in the rows of trees that seems to continue into the arched doorway of the courthouse.7

Plan of the city centre of Auch. Located in south-west France. Auch has an armature of interlinked urban spaces of varying spatial and functional character and mood endowing this little city with a public realm as richly diverse as that of a metropolis and which has remained visible over the centuries

And so on, and so on in a richly configured network of places of strikingly different character exactly apt in form and experiential quality to their use and location, an aptness matched by the forms and decorum of the civic institutions that face the squares and the institution facing them across yet another a square. What an ideal to keep in mind as we start to regenerate our cities to their full human purpose through urban design.

Busy square in Auch seen from town hall steps opening into the market square whose splay-sided foreshortening draws the cathedral forward

Footnotes

1. Pink, Daniel, A Whole New Mind: How to Thrive in the New Conceptual Age, Cyan Books, London, 2005. See essay in footnote 3.

2. Rifkin, Jeremy, The Third Industrial Revolution: How Lateral Power is Transforming Energy, the Economy and the World, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2011. See also review of this book by Peter Buchanan in AR January 2012.

3. Peter Buchanan, From Doing to Being, AR October 2006.

4. Peter Buchanan, What City? A Plea for Place in the Public Realm, AR November 1988.

5. For an extended and easily grasped explanation of the techniques and uses of Space Syntax see Space Syntax and Urban Design by Peter Buchanan in Norman Foster Works Volume 3, Prestel, 2007.

6. For more detailed discussion of World Squares for All see Peter Buchanan’s essay in Norman Foster: Works Volume 6, Prestel, 2013.

7. For an extended description and discussion of Auch see Auch: Organs of the Body Politic by Peter Buchanan, AR July 1987.

The Conclusion to The Big Rethink

The concluding Big Rethink essay will draw together the ideas put forward over the last year into a proposal for a new, 21st-century neighbourhood. Click here to read.

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design