Clayton Lockett and the World's Deepening Death-Penalty Divide

"As a very sincere friend, I think this is unworthy of the United States of America," one European lawmaker says.

Oklahoma's botched execution of Clayton Lockett on Tuesday night "showed vividly that the death penalty is a brutal form of punishment which disregards human dignity," the office of European Union High Representative Catherine Ashton told me in a statement on Wednesday. Lockett died after spending 45 minutes writhing in pain from an experimental drug cocktail that had been secretly obtained by state officials and not evaluated by medical professionals. Charles Warner, a second inmate who was scheduled to die the same night, received a temporary stay of execution from Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin, pending an investigation.

"The European Union is opposed to the use of capital punishment in all cases and under any circumstances," said Ashton, Europe's top diplomat, "based on the conviction that the death penalty is cruel, inhumane and irreversible, and its abolition is essential to protect human dignity." France's Foreign Ministry also issued a denunciation and urged Oklahoma and other U.S. states to impose a moratorium on executions.

The death penalty's universal abolition is a major EU foreign-policy objective, and EU officials have spoken out strongly against high-profile U.S. executions in the past. Ashton condemned the state of Texas in January for executing Edgar Tamayo Arias, a Mexican national, who had been denied the right to contact Mexican diplomatic officials during his arrest in violation of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations. EU agencies also fund U.S. groups opposed to the death penalty, while EU lawyers' briefs were cited by the U.S. Supreme Court when the justices forbade executing the mentally disabled in 2002 and minors in 2005.

The most successful effort in this arena came in December 2011, when the European Commission imposed an EU-wide export ban on certain drugs used in lethal injections, including pentobarbital and sodium thiopental, to the United States. U.S. manufacturers had already refused to sell drugs used in standard lethal injections to state prisons, citing ethical obligations. With their last major supply lines severed by Europe, corrections officials in multiple states turned to back-alley distributors overseas and then to poorly-regulated compounding pharmacies in the United States. Some states also changed their execution protocols to adjust to the supply shortage, substituting court-sanctioned drug cocktails with experimental ones.

Some suspect that a compounding pharmacy sold the drugs used in Lockett's execution, but Oklahoma Department of Corrections officials have refused to identify where they obtained them. Oklahoma Supreme Court justices, who had been threatened with impeachment by state lawmakers for delaying the two executions, lifted their stays of execution last week and denied a motion to force state officials to reveal the drugs' source. Similar legal challenges are still pending in other states that have refused to disclose their drugs' suppliers.

Sarah Ludford, a British member of the European Parliament and vice chair of its delegation to the U.S., helped craft the export ban in 2011 and spoke out forcefully against Oklahoma's actions. "It is hard to disagree with the reported comment of one lawyer that 'Clayton Lockett was tortured to death,'" Ludford told me in a statement. "As a very sincere friend, I think this is unworthy of the United States of America. The response to the EU ban on the export of certain drugs should not be to scrape the moral barrel."

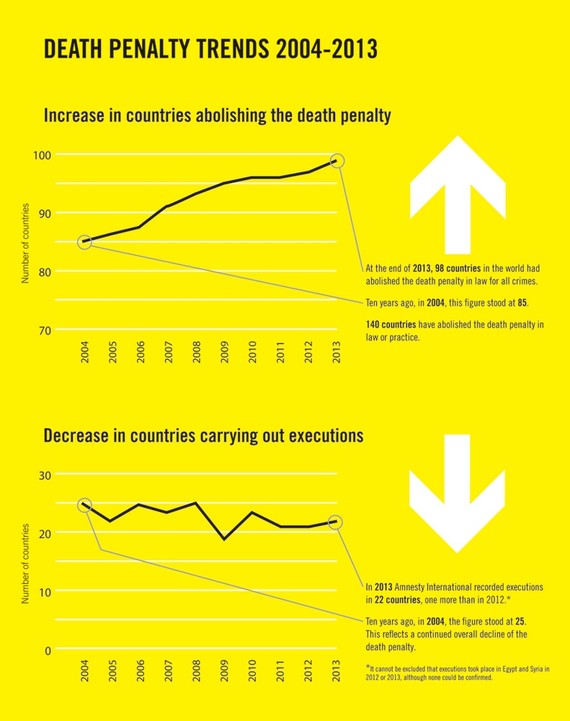

Internationally, the United States belongs to a dwindling club of countries that still perform executions. With the exception of Belarus, all European countries have formally abolished the practice, which is also becoming less common in Africa and Latin America, either in law or in practice. Russia's constitutional court enacted a moratorium on the death penalty in 1999, three years after the last execution there.

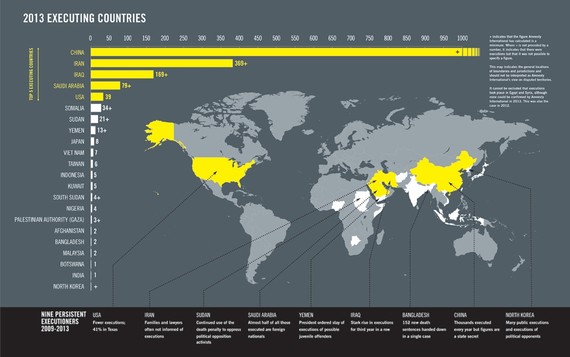

When the United Nations General Assembly called for a global death-penalty moratorium in 2012, U.S. delegates joined countries such as China, India, Iran, Japan, North Korea, Syria, and Zimbabwe in opposing the non-binding resolution. It ultimately passed with 110 countries voting in favor and 39 countries against. Only four countries—China, Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia—performed more executions than the U.S. in 2013, according to data gathered by Amnesty International. That year, the U.S. was the only country in the Western Hemisphere that carried out an execution.

Although polls show a majority of Americans still favor the death penalty, their once-staunch level of support has plummeted by nearly 20 percentage points over the last two decades. "The decisions about where to go from here have to be made by the American people," Ludford said, "but I hope a corner is being turned and that the end of capital punishment in all U.S. states will be hastened by the outrage at the resort to crude experimentation on human beings."